It is still a very experimental procedure, but it likely will be improved rapidly in the coming years and may become the standard approach one day.

There are nowhere near enough donated human organs to transplant into the number of patients who need them. As a result, many patients die well before an organ becomes available. Some 110,000 Americans are on transplant waiting lists and about 6000 die each year while waiting. In the case of kidneys, dialysis can often tide a patient over until a kidney becomes available. But the person who needs a heart transplant usually needs it fairly immediately and there are very limited means to maintain the patient’s life while waiting for the donor organ to become available. Most such heart failure patients die.

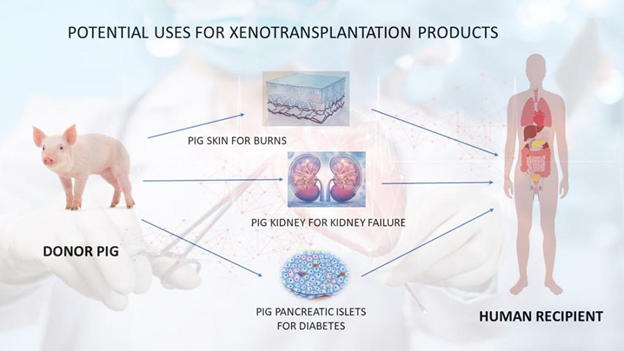

Xenotransplantation(i.e., transplanting from one species to another) has been the dream of transplant physicians for decades. The concept is to use an organ from an animal that can be placed into a human without it being immediately or later rejected by the patient’s immune system. Until recently, this was just a dream that scientists were actively following.

Just transplanting an animal’s organ into a human will not work. The person’s immune mechanisms will immediately reject the transplanted organ. So, what is to be done? The key is to genetically engineer the animal to produce organs that are less likely to be rejected. In the last 20 years, there’s been substantial progress on the research front to produce genetically modified pigs. Why pigs? Pig organs are about the same size as human organs but also share many physiologic similarities.

Recent technologies, including CRISPR, have allowed more possibilities to genetically engineer the pig’s genome. A few specific genes have been identifiedthat are critical. Some were modified and some inactivated, called “knocked out.” It’s not just a matter of changing the pig’s genetics, but it’s also having a very specific antirejection drug combination. This includes the standard drugs used to prevent rejection of human organs and a specially designed monoclonal antibody against a part of the immune system called CD 40. This monoclonal antibody has been found to be essential and critical to the successful transplantation of a heart in the nonhuman primate model with animals maintained without rejection for upwards of 900 days.

In September 2021, a xenograft kidney from a genetically engineered pig was placed in a brain-dead patient still on life support. It was observed for 58 hours at the New York University Langone Hospital Center with the family’s permission to study for evidence of function and rejection. As a result, the surgical and research team, led by Dr. Robert Montgomery, himself a donor heart transplant recipient, were able to obtain critical information about the pig organ after transplantation. “Whole-body donation after death for the purpose of breakthrough studies represents a new pathway that allows an individual’s altruism to be realized after brain death declaration in circumstances in which their organs or tissues are not suitable for transplant.”

On Friday, January 7, Bartley Griffith, MD, Muhammad Mohiuddin, MD, and an extensive team of multi-specialties successfully implanted a genetically modified pig heart obtained from the Revivicor company. Revivicor created the genetically modified pig and hence the heart to the investigators’ specifications. This included modifying ten genes with three knocked out that lead to antibody development and one knocked out that controls the pig organs’ growth. The patient will also receive various antirejection drugs plus the monoclonal antibody aimed at CD40.

The patient, a 57-year-old man, was on life support and not eligible for a human donor organ. His projected lifespan was in days to weeks. He understood the risks of the procedure and that it was a first-time human experiment. But as he said before surgery, “It was either die or do this transplant. I want to live. I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice… I look forward to getting out of bed after I recover.” The Food and Drug Administration (FDA,) having reviewed the research data, authorized the procedure “for compassionate use” on New Year’s Eve. As of Tuesday, January 12, the patient was doing well with no evidence of rejection. Only time will tell if he will make a full recovery and have his pig heart perform for many years.

Dr. Griffith is a cardiovascular surgeon with years of experience in transplanting human hearts and lungs. He has been working on xenotransplantation for over a decade. Dr. Mohiuddin joined with Dr. Griffith at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and Medical Center about five years ago to further pursue his research from the National Institutes of Health. He and colleagues developed the initial techniques to prevent rejection by gene modifications and antirejection drugs.

Together Griffith and Mohiuddin established the Xenotransplantation Center with Griffith as clinical director and Mohiuddin as scientific director. But, of course, there is a large team, not just the two of them. The Center investigators received a $15.7 million sponsored research grant to evaluate Revivicor genetically-modified pig hearts in further baboon studies. This was the current cumulation of those studies with a first in human heart xenotransplantation.

A new dawn has likely arrived for organ transplantation. But, of course, this was only the first patient, and it remains to be seen how effective it will be in this man or how effective it will be in others treated with other genetically engineered pig organs like kidneys, pancreas, or lungs. But without question, it’s an exciting time with transplant-waiting individuals having a new potential on the horizon for returning to a reasonably normal life.